Classical Comments: Eustyle

By: Calder Loth

Senior Architectural Historian for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources and a member of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art’s Advisory Council.

Source: http://blog.classicist.org/

Figure 1. Pantheon portico, Rome; an ancient example of eustyle intercolumniation (Loth)

In The Ten Books on Architecture, the famous (and only surviving) ancient treatise on architecture, its author, Vitruvius, discusses how the character of a temple portico can be affected by the spacing of its columns. Vitruvius defines closely spaced columns pycnostyle, which means the column shafts are spaced one and a half column diameters apart. This gives a portico a very static appearance. The widest spacing is araeostyle, which is four diameters apart. Vitruvius tells us araeostyle is impossible with masonry construction because the spans are too great for stone architraves. Areaostyle spacing is practical only when architraves are composed of wooden beams. Other types of intercolumniation are systyle (two diameters apart) and diastyle (three diameters apart). In all four spacing types, the columns have equal-width spaces between them.

Vitruvius then informs us that the ideal intercolumniation system is eustyle. As defined by Vitruvius, a eustyle portico has bays that are two and a quarter diameters in width except for the center bay, which is three diameters wide. Vitruvius proclaimed the superior quality of eustyle spacing, stating, “In this way, the temple will have a beautiful configuration with no obstruction at the entrance.”[1] The term eustyle is derived from the Latin prefix eu, meaning good (as in euphoria—feeling good), and the Latin stilus, a narrow cylindrical object; i.e., a column shaft. The principle of eustyle spacing can be applied to porticos of four (tetrastyle), six (hexastyle), and eight (octastyle) or more columns.

Figure 2. Pantheon portico (detail), ‘The Four Books’ (Isaac Ware edition, 1738) Book 4, plate LI

In perusing Book 4 of Andrea Palladio’s Quattro Libri (Four Books on Architecture), we might note that the majority of the ancient porticoed temples in Palladio’s reconstruction drawings incorporate some form of eustyle spacing. Among them is the Pantheon, where Palladio notes that the portico’s center bay, in Vincentine feet and inches,[2] is 9’3½” wide, while the outer bays are 8’2½”wide. (Figure 2) Even though the temples Palladio measured and illustrated normally employ a slightly wider center bay, not all strictly follow Vitruvius’s spacing formula. Indeed, in some of the temple elevations, such as that for the Temple of Saturn, the dimension variation is so subtle that we need to look very carefully to see the effect. (Figure 3) Except for the Ionic temples of Portunus[3] and Saturn,[4] all of the porticoed temples Palladio included in Book 4 are in the Corinthian order, the preferred order for major buildings of the Roman imperial period.

Figure 3. Temple of Concord (Saturn), ‘The Four Books’ (Isaac Ware edition, 1738) Book 4, plate XCIII

Palladio employed some form of eustyle spacing in virtually all of his portioced villa and palace designs published in Book 2 of Quattro Libri. Because of the small scale of several of his villa elevations, as illustrated in the original woodcut prints, the eustyle spacing is not readily apparent. We see this in his elevation of the Villa Emo, where eustyle is not depicted. (Figure 4) However, as built, the villa subtly incorporates eustyle spacing in its Tuscan portico. (Figure 5) Palladio made no secret of his preference for eustyle intercolumniation. In Chapter IV of Book 4 of Quattro Libri, Palladio paraphrased Vitruvius thusly: “So, then, the most beautiful and elegant sort of temple is called eustyle, which occurs when the intercolumniations are two and quarter column diameters, because it is extremely practical and also provides beauty and strength.”[5]

Figure 4. Villa Emo, (detail), ‘Quattro Libri’ (Tavenor and Schofield translation of the 1570 edition), Book II p. 55

Figure 5. Villa Emo, Fanzolo, Italy (Loth)

Among the aesthetic advantages of eustyle intercolumniation is the subliminal focusing of attention on a building’s entrance. We see this in an almost subconscious way in each of the porticos of Palladio’s Villa Rotonda. (Figure 6) More importantly, making use of eustyle spacing can correct an optical illusion. Consider, for example, the Tuscan portico of the 1826 Goochland County courthouse with its areaostyle (four diameters) column spacing. (Figure 7) Although the portico’s three bays are exactly the same width, the center bay appears narrower—an optical illusion. In contrast, the similar Tuscan portico on the 1823 Frascati makes use of eustyle intercolumniation. (Figure 8) As with the Villa Emo, Frascati’s eustyle spacing lends a more visually pleasing character to the composition even though it is not immediately apparent that the center bay is wider, especially if not viewed straight on.

Figure 6. Villa Rotondo, Vicenza, Italy (Loth)

Figure 7. Goochland County Courthouse, Goochland, Virginia (Loth)

Figure 8. Frascati, Orange County, Virginia (Loth)

Both the Goochland Courthouse and Frascati were designed and built by master builders who had worked for Thomas Jefferson at the University of Virginia. There they learned the classical language, but not necessarily a consistent use of eustyle spacing. Despite his strong advocacy of Palladian forms, Jefferson applied the eustyle principle only rarely. His Pavilion V at the University of Virginia is the only one of the institution’s ten pavilions to have eustyle spacing. (Figure 9) Here the hexastyle Ionic portico bears a strong resemblance to the porticoes of the Villa Rotonda, a work that was an important inspiration for Jefferson. Jefferson headed his handwritten specification notes on the pavilion: “Pavilion No.V. Palladio’s Ionic modillion order.”[6] His awareness of eustyle is evident further down in the notes where he wrote: “from cent. to cent. of Columns mod 3 1/3 gives intercol. of mod. 2 1/3 the eustyle being 2 ¼ mod . . .”[7] Jefferson also used barely perceptible eustyle spacing in his proposed design for the residence of the United States President, a scheme based on the Villa Rotonda.

Figure 9. Pavilion V, University of Virginia (Loth)

The 18th-century English Palladian architects were more consistent with their advocacy of Vitruvius’s and Palladio’s preference for eustyle spacing. A majority of the portioced designs in Colen Campbell’s Vituvius Britannicus (1715 & 1725) have eustyle intercolumniation. Sir William Chambers discussed some of the issues of eustyle in his Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture. “It is however to be observed, that if the measures of Vitruvius be scrupulously adhered to, with regard to the eustyle interval, the modillions in the Corinthian and Composite cornices, and the dentils in the Ionic, will not come regularly over the middle of each column. The ancients, generally speaking, were indifferent about these little accuracies.” [8] Chambers went on to explain how to deal with the problem by making the column spacings slightly wider. Perhaps Campbell and Chambers were inspired by Inigo Jones, the patron saint of the Anglo-Palladian movement, who employed eustyle spacing conspicuously in the loggia on the Queen’s House, Greenwich (1616-35), a herald of English Palladianism. (Figure 10)

Figure 10. Queen’s House, Greenwich, England, ‘Vituvius Britannicus’, Vol. 1, plate 15

The Anglo-Palladian architect, James Gibbs, on the other hand, was less concerned with eustyle design. He is silent on the subject in his otherwise highly influential Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1732). Moreover, nearly all of Gibbs’s portioced designs in A Book of Architecture (1728) lack eustyle spacing. Even his most famous work, St. Martin in the Fields (1722-26) avoids eustyle spacing, a design that influenced hundreds of American churches. (Figure 11) We might note, however, that in one of the most faithful adaptations of St. Martin, the 1924 All Souls Unitarian Church in Washington, D.C., architect Henry Shepley applied eustyle spacing in its Corinthian portico. (Figure 12) Shepley may have been adhering to Chambers’ advice on how to handle the eustyle principle with the Corinthian order. More likely, he was following William R. Ware’s instructions in The American Vignola, the textbook for nearly every American architect of the first half of the 20th century. Ware wrote,

“The ancients . . . preferred what they called Eustyle Intercolumniation, of two and one-half Diameters (or three and one-half Diameters on centers, in place of three Diameters). But the moderns prefer to make the Eustyle Intercolumniation two and one-third Diameters (setting the columns three and one-third Diameters on centers), as this brings even Columns in Ionic and Corinthian colonnades exactly under the Dentil, and every alternate one just under a Modillion, the Dentils being one-sixth of a Diameter on centers, and Modillions two thirds of a Diameter.” [9]

If we look carefully at All Souls’ portico, we can see that each column is centered under a modillion.

Figure 11. St. Martin in the Fields (detail), James Gibbs, ‘A Book of Architecture’, plate 3

Figure 12. All Souls Unitarian Church, Washington, D.C. (Loth)

Eustyle spacing is not so accommodating for the Doric order. If a column is to be properly centered beneath a triglyph, the middle bay cannot be widened without adding an extra triglyph, thus precluding any chance for a less pronounced increase in spacing in the center. We see this in comparing the porticos of Monticello (Figure 13) and the Redwood Library. (Figure 14) Monticello’s portico bays are the same width, but even here, the center bay appears narrower than the flanking bays. The entablature in the Redwood Library’s center bay employs the extra triglyph resulting in the center bay being conspicuously wider.

Figure 13. Monticello portico (Loth)

Figure 14. Redwood Library, Newport, Rhode Island (Historic American Buildings Survey)

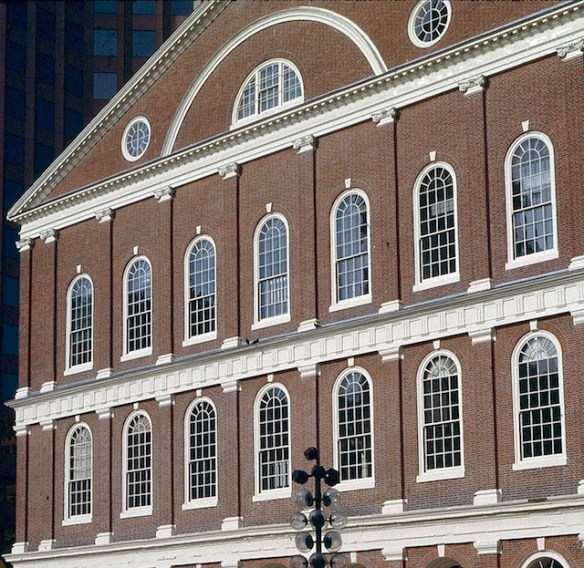

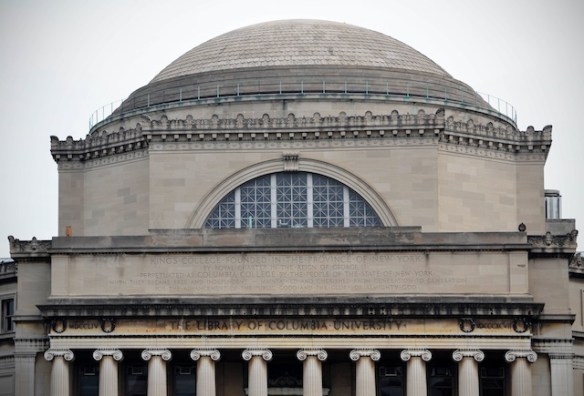

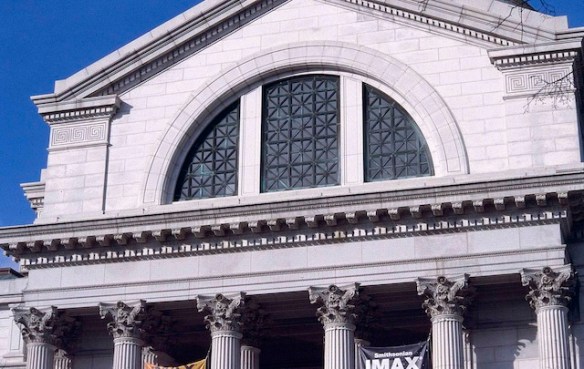

An awareness of the ancient principle of eustyle intercolumniation prompts us to take a more careful notice of the numerous porticoes we encounter. Many of the great landmarks of the American Renaissance employ eustyle spacing, including the Columbia University Library, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Supreme Court. John Russell Pope did not overlook the effectiveness of this age-old principle in what is perhaps the nation’s most prodigious Corinthian portico, on the National Archives. (Figure 15) Oftentimes the effect is so subtle that, like the Pantheon, it is more felt than seen.

Figure 15. National Archives, Washington, D. C. (Loth)

[1] Thomas Gordon Smith, Vitruvius on Architecture, (The Monacelli Press , 2003) p. 96

[2] Though various Renaissance texts vary, the Vincentine foot is approximately 13.5 inches imperial.

[3] Called by Palladio the Temple of Fortuna Virilis.

[4] Called by Palladio the Temple of Concord.

[5] Andrea Palladio, The Four Books on Architecture, Translated by Robert Tavenor and Richard Schofield, (MIT Press, 1997) p. 219.

[6] Mesick-Cohen-Waite Architects, Pavilion V, Historic Structure Report (University of Virginia, 1994) p. 20.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Sir William Chamber, A Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture (2003 Dover Publications reprint of the London, 1791 third edition) p. 81.

[9] William R. Ware, The American Vignola (1994 Dover Publications Reprint of the 1903 edition) p. 47.