By Calder Loth

By Calder Loth

Senior Architectural Historian for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources and a member of the Institute of Classical Classical Architecture & Art‘s Advisory Council.

Courtesy of: the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art blog.classicist.org/

Dedicated in 306 A.D., the Baths of Diocletian survive as Rome’s only relatively intact ancient bath structure. Its main space, the vast vaulted frigidarium,[i] was preserved by conversion to a church under the direction of Michelangelo in 1563-64.[ii] A distinctive feature of the frigidarium is the series of huge windows along the upper tier of its side walls. (Figure 1) The window form consists of a large semi-circular arch divided into three sections by two thick vertical mullions.[iii] Because of their association with this structure, windows in this configuration are termed Diocletian windows, but we also describe them as thermal windows from thermae, the Latin word for warm bath. The windows’ brick construction was originally veneered with stone moldings and decorations of which only fragments remain in situ. Nevertheless, the form appealed to Renaissance architects who popularized it through treatises and projects. As we see in the following survey, architects have interpreted and applied the Diocletian window in a variety of ways over the past four and a half centuries.

Figure 1. The Baths of Diocletian, Rome (Loth)

Figure 2. Villa Foscari, Italy (Loth)

Andrea Palladio undertook detailed studies of Roman bath ruins with the intention of producing a book on the subject. His project never materialized but various features observed in the ruins found their way into several of Palladio’s designs.[iv] The Diocletian window appears in three of Palladio’s villa elevations published in Book II of I Quattro Libri (1570). Perhaps Palladio’s most prominent Diocletian window dominates the rear elevation of the ca. 1560 Villa Foscari, also known as La Malcontenta. (Figure 2) We have no published drawing of the rear; Palladio’s treatise illustrates only the villa’s portioced façade. Nevertheless, like the ancient prototype, the villa’s huge window is reduced to essentials. Its only ornament is the rustication joints scribed into the stucco.

Figure 3. San Moisè, Venice (Loth)

Palladio set a precedent for incorporating a Diocletian window into the façades of Venetian churches with his designs for San Francesco della Vigna (1566-70) and S. Maria della Presentazione, also known as Le Zitelle, (1577-80). Palladio also incorporated Diocletian windows in the clerestory of Il Redentore (consecrated 1592). The tradition extended to several later Venetian churches including the façade added in 1688 by Alessandro Tremignon to the church of San Moisè, perhaps the most luscious Baroque façade in Venice. (Figure 3) Though hardly small, the Diocletian window above the entrance is almost overwhelmed by its Baroque encrustations. The window itself is set well back from the heavily decorated arch and mullions. With its sculptures by Heinrich Meyring, the façade is a monument to the Fini family, its patrons.

Figure 4. Gibbs Building, King’s College Cambridge: James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture (1728), plate 34.

In 1724, architect James Gibbs received the commission to design a complex of buildings for the front court of King’s College, Cambridge. Of the three massive structures in Gibbs’s scheme only the West Range, built 1724-31, was realized. For the central pavilions of each front, Gibbs proposed a broad Diocletian window atop a Doric aedicule framing the entrance arch. (Figure 4) This composition closely followed Palladio’s final design for the Villa Pisani at Bagnolo shown in Book II of I Quattro Libri.[v] As illustrated in Gibbs’s A Book of Architecture (1728), Gibbs intended the pediment slopes of the King’s building to be adorned with statues of reclining scholars in the manner of the figures on Michelangelo’s Medici tombs. The sculptures were never realized. Gibbs proposed a similar combination Diocletian window and portico for Whitton Place, Middlesex, but his design was rejected in favor of a design by Roger Morris.[vi]

Figure 5. Chiswick, London (Loth)

Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, was the primary leader of England’s 18th-century Anglo-Palladian movement. His passion for the architecture of Andrea Palladio and his contemporaries inspired his design for his villa at Chiswick. (Figure 5) Completed in 1729, the compact structure exhibited in its forms and details Lord Burlington’s broad knowledge of Palladian architecture. Burlington crowned his house with an octagonal dome prominently fitted with Diocletian windows on its four main faces. The use of this motif was likely inspired by one of Palladio’s early schemes for the Villa Pisani at Bagnolo, the drawing for which was among Burlington’s large collection of original Palladian drawings. (Figure 6) The stair and inset Palladian window in the drawing are features also reflected in Chiswick.

Figure 6. Andrea Palladio, Preliminary design for the Villa Pisani at Bagnolo; pen and brown ink drawing, ca. 1542. (Royal Institute of British Architects)

Figure 7. Mount Clare, Baltimore (Loth)

The lunette in the pediment of Baltimore’s Mount Clare is among America’s very rare Colonial-era versions of the Diocletian window. (Figure 7) Unlike the more standard half-circle examples, Mount Clare’s window is a shallow segment supported with the requisite pair of vertical mullions to give it the thermal form. The voids between the mullions are backed with small window panes. Mount Clare was erected in 1760 as a villa with an extensive park and terraced garden for Charles Carroll, a prominent Maryland patriot. As seen in the illustration, the house walls are laid in header bond, a characteristic feature of the finest colonial Maryland dwellings.

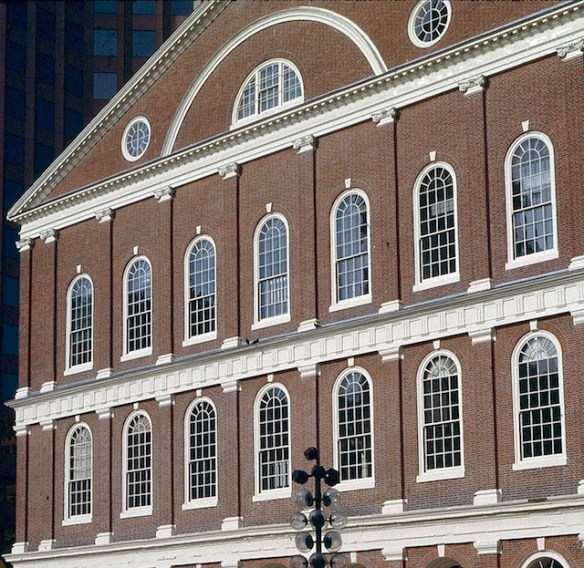

Figure 8. Faneuil Hall, Boston (Loth)

The Diocletian window enjoyed increased though limited popularity during the Early Republic. Boston architect Charles Bulfinch installed them in a handful of his buildings, including his 1805 expansion of the 1742 Faneuil Hall in the heart of Boston. (Figure 8) Bulfinch’s remodeling involved increasing the original three-bay façade to seven bays and adding the tall third story. To accent the resulting vast pediment, Bulfinch inserted a Diocletian window flanked by two circular windows. Bulfinch gave prominence to the somewhat diminutive Diocletian window by framing it in a broad curved architrave, a trick he used in other designs and one that works effectively in this prodigious structure.

Figure 9. Former Bourse, St. Petersburg, Russia (Loth)

Architect Thomas de Thomon used the Diocletian window with dramatic flair in the attic gable of the St. Petersburg Bourse (Stock Exchange), a monumental landmark on the prow of Vlasilyevsky’s Island, across the Neva from the Winter Palace. (Figure 9) A multiplicity of thin voussoirs forming the arch gives the window the effect of a radiant sun rising from the portico. Partly hiding it, however, is S. Sukhanov’s sculpture group of Neptune with Two Rivers. Surrounding the building is a peristyle of forty-two unfluted Greek Doric columns, an echo of Paestum. The strategically sited structure served as the center of financial and trade operations for Imperial Russia. Since 1940, the building has housed the Central Naval Museum.

Figure 10. Imperial Stables and Carriage House, Pushkin, Russia (Loth)

We see a more lighthearted use of Diocletian windows on the Imperial stables in Pushkin (formerly Tsarskoye Selo), the suburban town of palaces and parks south of St. Petersburg. (Figure 10) Rendered in Russia’s virile Neoclassical style, the 1820 stable complex was designed by Vasily Stasov and Smaragd Shustov. Here a series of windows punctuates the façade of the stable courtyard. Setting off each window is a thick, plain lintel painted white to contrast with the tan stucco. The curved lintels reflect the semi-circular plan of the courtyard. The battered doorway and keystone focus attention on the center window. Vasily Stasov is best known as the architect of the Winter Palace staterooms, rebuilt after the fire of 1837.

Figure 11. Fireproof Building, Charleston, South Carolina (Loth)

Architect Robert Mills incorporated a Diocletian window in the Meeting Street elevation of the Fireproof Building, constructed 1820-27 as a state office building. (Figure 11) It quickly became known as the Fireproof Building because of its pioneering use of non-combustible materials to protect government records. Though he was a dedicated classicist, Mills used the Diocletian motif in only a few instances. His mentor, Thomas Jefferson, interestingly, applied the motif to none his buildings. In the Fireproof Building, Mills tied the window into a composition embracing the three-part window below. Accenting it is a decorative iron railing, giving a lightness to an otherwise visually solid structure.

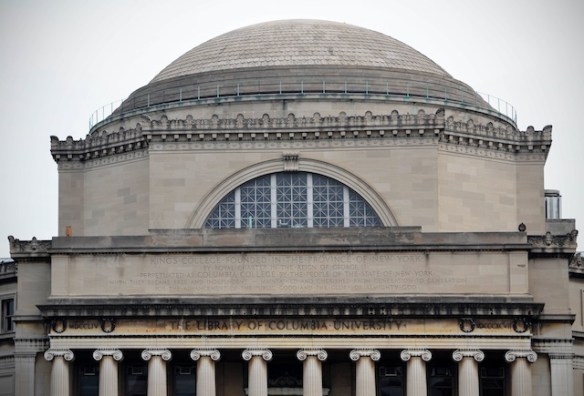

Figure 12. Low Memorial Library, Columbia University, New York City (Loth)

The firm of McKim, Mead & White made use of the Diocletian window in a variety of forms in numerous projects. In two of the firm’s most monumental works: Pennsylvania Station (1906-10; demolished 1964) and Columbia University’s Low Memorial Library (1893-95), the widows were of such huge scale that they were divided by four vertical mullions rather than the more standard two. (Figure 12) The use of four mullions at Low Library may have been dictated by the fact that the mullions are metal rather than thick masonry. Nevertheless, with the window panes set in Roman lattice, the broad composition has a gracefulness despite its size.

Figure 13. Bavarian State Chancellery, Munich, Germany (Loth)

The heavy classicism of Imperial Germany, known as the Wilhelmine style, is boldly exhibited in the central domed section of what is now the Bavarian State Chancellery in Munich. (Figure 13) At the base of the dome is a pedimented pavilion framing a rusticated Diocletian window, a weighty contrast to the window in the Natural History Museum shown below. Designed by Ludwig Mellinger, the building’s center section is all that remained of the 1905 Bavarian Army Museum following the Allied bombing in World War II. The destroyed wings were rebuilt in 1992 in glassy greenhouse style to house the state legislature and government offices.

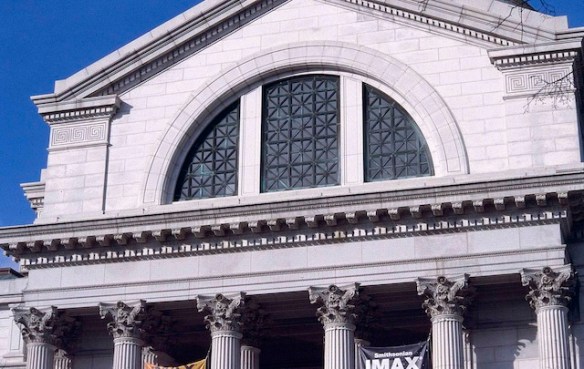

Figure 14. Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C. (Loth)

The firm of Hornblower and Marshall provided our National Mall with a classic Diocletian window set in the open tympanum pediment of the Natural History Museum, built 1901-11. (Figure 14) The allusion to classical Antiquity is reinforced by the use of bronze Roman lattice in the openings. Executed in white granite, the window’s plain architrave frame and vertical mullions lend the composition a restrained monumentality. Below the window is a hexastyle colonnade employing the Corinthian order of the Temple of Castor and Pollux, the three columns of which survive in the Roman Forum. The museum’s pediment and window is one of four identically treated pediments providing buttressing for the dome of this monument of the American Renaissance.

Figure 15. Memorial Gymnasium, University of Virginia, Charlottesville (Loth)

The ancient Roman baths provided excellent precedents for enormous formal enclosures such as railroad stations and gymnasiums. We see this in the University of Virginia’s Memorial Gymnasium, whose form was inspired by the Baths of Diocletian. (Figure 15) Completed in 1924, the design was the product of an architectural commission with Fiske Kimball, founder of the university’s school of architecture, serving as supervising architect. As with the Diocletian bath’s frigidarium, Memorial Gymnasium’s side elevations are composed of a series of gables supporting huge Diocletian windows. The gymnasium’s brick construction reflects the brick walls of the Roman baths, stripped of their stone veneers.

Figure 16. Brooks Brothers Store, Beverly Hills, California (Loth)

[i] The frigidarium was the main space in the bath complex. It was so termed because it contained a series of pools for cold baths.

[ii] The church name is the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri. It was further embellished by architect Luigi Vanvitelli in 1749.

[iii] The bottoms of the arches, where the curve meets the lintel, have been infilled with masonry for extra support, giving the arch a slightly stilted look.

[iv] Palladio’s drawings of the baths were eventually published by Lord Burlington in 1730, and by Charles Cameron in 1772.

[v] The portico proposed for the Villa Pisani was not built but the Diocletian window is intact.

[vi] Terry Friedman, James Gibbs (Yale University Press, 1984), p. 317.