Source: http://www.traditionalbuildingportfolio.com/projects/residential/greekexcursion.html

Greek Excursion

A run-down house in Massachusetts is reborn as a Greek Revival residence.

Project: Residence, Weston, MA

Architect: Jan Gleysteen Architects, Wellesley, MA; Jan Gleysteen, NCARB, AIA, principal

By Annabel Hsin

On a picturesque Saturday morning, architect Jan Gleysteen and his son drove to the quaint coastal Maine town of Wiscasset to visit a collection of Greek Revival houses built between 1820 and 1845. They spent the afternoon photographing, measuring and documenting various architectural details and conducted case studies of four houses. The research was for a project in Weston, MA, in which the owners of a run-down Cape structure approached Gleysteen, principal of Wellesley, MA-based Jan Gleysteen Architects, with the goal of rebuilding their house.

“The clients came to me and said they wanted a Greek Revival house that reflects early American democracy,” says Gleysteen. “I’d never designed a Greek Revival, but had studied the style when I was a student under Robert Stern, who told us to go and measure everything. By the time I received this assignment a couple of decades later, I had the academic orientation to go about designing this house.

“There are many Greek Revival examples in Weston, but I did most of my research in Wiscasset because it’s a beautiful town and there are more than a dozen houses side by side,” he adds. “I could compare one house to another, and I found very little variation, so it gave me a basis of confirming that the dimensions were correct. Whereas in Weston, the houses were scattered, and it was an agrarian community until the late-19th century.”

Adjacent to a 30-acre communal farm, the site is located on a busy road with restrictive zoning. In order to comply with the zoning restrictions, a small portion of the original house and most of the original foundations were retained. “Even though there was virtually nothing left of the original house, which was in terrible condition,” says Gleysteen, “we had to build a new home on the existing foundation.”

The program called for the space of a typical five-bedroom suburban house with a kitchen, living, dining, family and breakfast rooms as well as a pantry, mudroom and two-car garage, resulting in a 4,800-sq.ft. structure. To disguise the home’s true size, Gleysteen split the program into two back-to-back gabled wings and arranged them in a pinwheel plan to enclose a hidden, flat rooftop at the center.

“The key to the scale was to not allow the roof ridge to keep rising up,” says Gleysteen. “On the front façade, the roof ridge stops at 15 ft. but the depth of the house is 47 ft. If we placed the ridge in the middle, like most houses, it would be 24 ft. high. When viewed from any angle, our depth illusion is what appears to be a 2,000-sq.ft. house.”

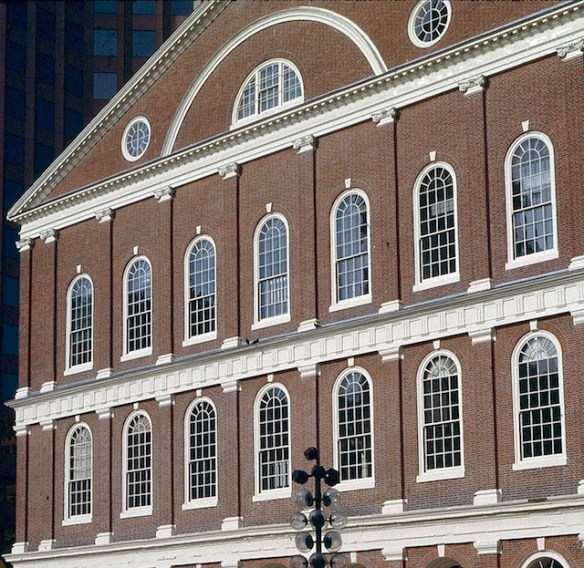

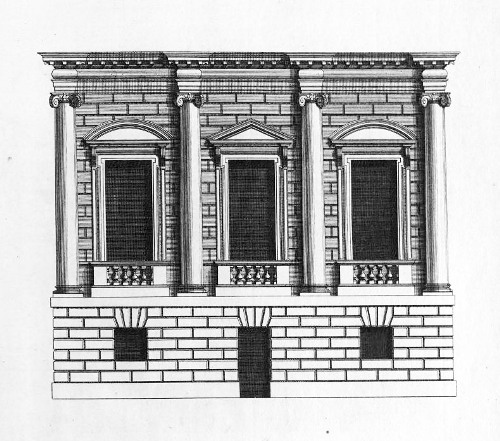

Below the roofline, details from the Wiscasset case studies were replicated on the exterior. The front elevation consists of a main gable and a side porch with the main entry placed at the center. The façade is complemented with recessed corner pilasters, western red cedar siding and double-hung windows with operable shutters as well as surrounds that were inspired by the temple form. Beneath the porch, there are fluted Doric columns, triple-hung windows and a French side door with exaggerated crossbars to resemble the windows. Above the second floor, a tall horizontal frieze extends across the entire façade. The rear elevation contains identical details but the main gable is placed at the center and the porch is replaced with a pergola and three sets of French doors; a bluestone terrace completes the outdoor gathering space.

“The half-round windows on the elevations were idiosyncratic design elements from the early-19th century that aren’t repeated today,” says Gleysteen. “Today, those would be perfect half-round windows. Instead, these have a large solid starting base for the spoke mullions to meet; it’s more of a sunburst. The other unique detail is the oval attic windows – a coastal variation inspired by maritime portholes on a sailing ship.”

Through the main entry, the foyer, parlor, library alcove and dining room make up the formal living spaces and contain Greek Revival details that were rigorous in their replication. The dining room features crown molding, wainscoting and window casings with operable angled shutters. The door surround supports an over-scaled crown that was another detail of the style inspired by Egyptian forms.

Toward the rear, the family room and kitchen share a large open space. The family room is one-and-a-half stories high with two levels of windows and French doors to allow natural light in. Its focal point is a fireplace with Classical details, Doric columns and a mirror resembling a temple above the mantel.

At the center of the kitchen, a large island is topped with marine-grade, finished teak. Shaker-style cabinets and imported Bahia blue granite countertops complement the large window over the sink. A bead-board ceiling and an exaggerated crown housing recessed lights complete the room. White oak floors were installed throughout to unite the casual and formal spaces.

“The island is the most important element in our kitchen designs,” says Gleysteen. “In this case, we designed a center panel for the chandeliers over the island to strengthen the central space. Each light attaches to the panel that has a stepped profile, which was influenced by Art Deco – the style correlates with Greek Revival in its use of geometry.”

Adjacent to the kitchen, the mudroom is treated as a second front door with accommodations for closets, cubbies, a bathroom and access to the garage. Antique limestone was installed in an ashlar pattern on the floor and the steps leading to the garage are bluestone.

The use of classic Beaux Art axial geometry improves the interior flow and draws attention to the exterior views. “When you enter from the garage, you’re on axis to the kitchen that leads to the family room and ends with a window,” says Gleysteen. “Conversely, through the front door to the left, you can look straight through into the family room and there’s a glimpse of the rear yard beyond. There’s another sightline from the dining room, through the butler’s pantry, to the large window over the kitchen sink.”

Upstairs, the master suite – consisting of a bedroom, dressing room, master bath and a large study – along with two other bedrooms, a bathroom, an additional bedroom suite and a laundry area, are organized around the central hall, which is illuminated by a skylight. Light fixtures beside the skylight are set in panels with the same design as the one above the kitchen island. The ceiling is accentuated with a distinctive cove-shaped Greek key molding below the crown.

Key manufacturers and suppliers for the project included Wausau, WI-based Kolbe & Kolbe Millwork (windows); Wilmington, NC-based Chadsworth Columns; Montgomeryville, PA-based Tim-berlane (shutters and shutter hardware); Branchburg, NJ-based Hahn’s Woodworking Company (garage doors); and Portland, OR-based Rejuvenation (interior lighting).

“This project was a labor of love,” says Gleysteen. “We’re very passionate about historic American architectural styles and it was a really fun adventure. We’re pleased about the rigorous research we conducted, having the chance to measure everything and using our background in construction detailing to replicate these details. This project is a rarity because not everyone does it, and I would love to see more Greek Revival-inspired architecture built.”

Jan Gleysteen Architects of Wellesley, MA, renovated a run-down Cape structure in Weston, MA, to reflect Greek Revival precedents and early American democracy. The 4,800-sq.ft. house comprises a kitchen, living, dining, family and breakfast rooms as well as a pantry, mudroom and two-car garage. All photos: Sam Gray

The one-and-a-half-story family room shares an open space with the kitchen. It features two levels of windows and French doors, as well as a Classically-detailed fireplace.

A marine-grade, finished-teak island anchors the kitchen. White oak floors unite the casual and formal spaces and complement the bead-board ceiling and Shaker-style cabinets.

A skylight illuminates the second-floor central hall, around which the master suite, two bedrooms, a bathroom, an additional bedroom suite and a laundry area are organized.

As viewed from the main entry, the dining room contains Greek Revival details such as crown molding, wainscoting and window casings with operable angled shutters. The door surround supports an Egyptian-inspired over-scaled crown.